Disease State

Prevalence and Etiology

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a prevalent chronic inflammatory skin disorder in dogs, affecting approximately 10–15% of the canine population globally.1,2 AD is responsible for nearly 60% of canine dermatological diagnoses in veterinary practice.2 AD most commonly manifests in young to middle-aged dogs, with clinical onset typically occurring between 1 and 3 years of age. In certain geographical regions, the prevalence of AD surpasses that of flea allergy dermatitis.3

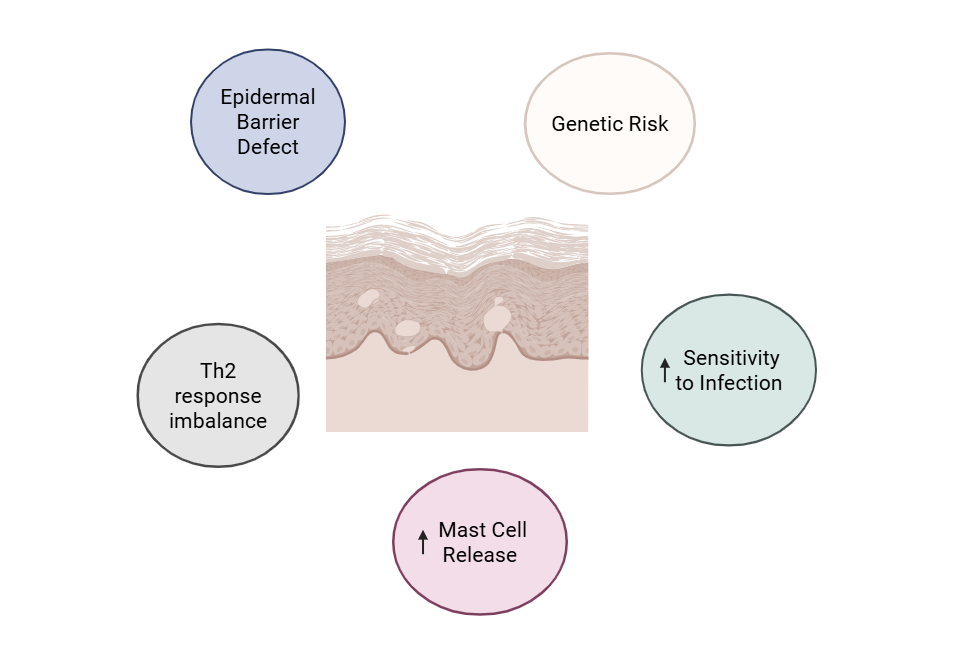

Multiple risk factors contribute to the development of canine atopic dermatitis (CAD), including2,4–6:

- Genetic predisposition with a higher incidence of AD diagnosed in Labrador Retrievers, Golden Retrievers, and West Highland White Terriers7

- Epidermal barrier dysfunction leading to increased transepidermal water loss and enhanced allergen penetration

- Imbalanced T-lymphocyte cytokine responses, particularly a Th2-skewed immune profile8

- Elevated cutaneous mast cell degranulation contributing to local inflammation and pruritus

- Increased susceptibility to secondary bacterial and yeast infections due to trauma from itching

The multifactorial etiology and combination of unique factors in each patient can make CAD difficult to diagnose and treat.

Immunology

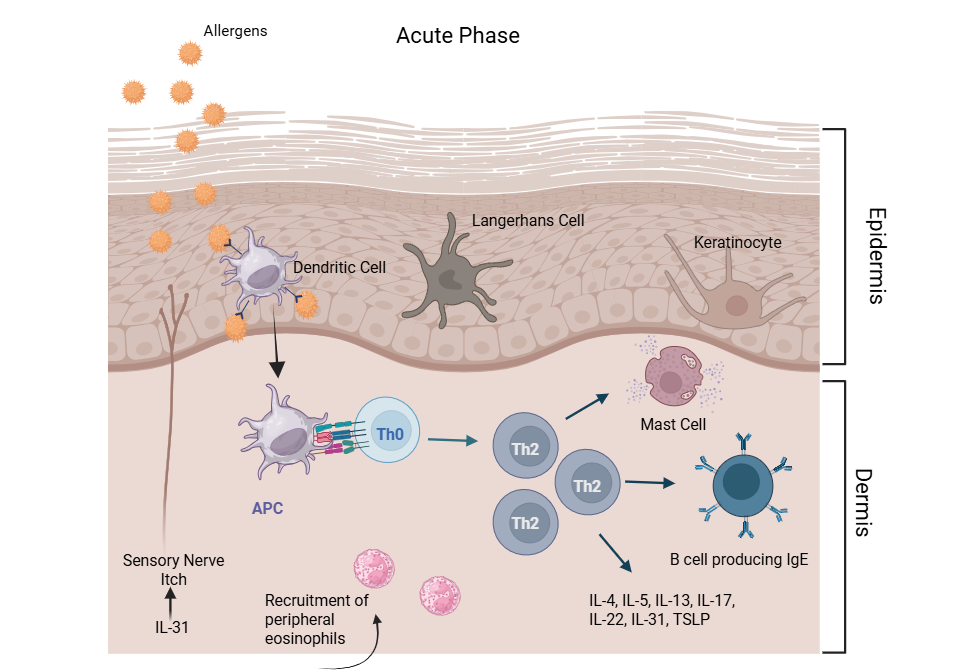

The immunopathogenesis of CAD is driven by dysregulated activation of T helper 2 (Th2) lymphocytes, which play a central role in initiating and perpetuating skin inflammation. Th2 cells secrete a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-17, IL-22, IL-31, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP). These cytokines contribute to epidermal barrier dysfunction and promote cutaneous inflammation.

Among these cytokines, IL-31 is particularly noteworthy for its role in pruritus.10 IL-31 binds to its receptor on peripheral sensory neurons, triggering pruritogenic signaling and promoting itch perception in both dogs and humans.11 It is highly upregulated following epicutaneous allergen exposure in dogs sensitized to house dust mites.10

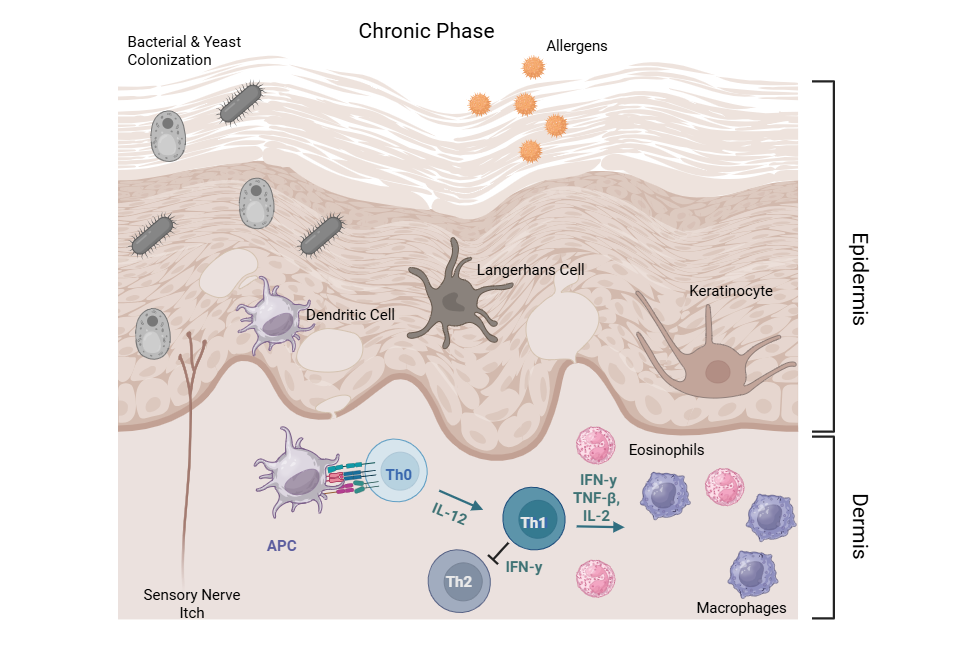

CAD is characterized by distinct acute and chronic immunologic phases:

- Acute Phase8: Lesions are predominantly infiltrated by Th2 lymphocytes. Activated Th2 cells secrete cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, IL-13) that promote B cell class switching to IgE, stimulate eosinophil recruitment, and induce mast cell degranulation. These responses culminate in immediate hypersensitivity reactions and amplify the inflammatory cascade.

- Chronic Phase8: Chronic lesions show a mixed Th1/Th2 profile, with increased Th1 cell infiltration. Resulting Th1 cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-beta (TNF-β), and IL-2 mediate delayed-type hypersensitivity and sustain cellular inflammation by activating macrophages and cytotoxic T cells. IFN-γ also acts to downegulate Th2-mediated IgE synthesis, reflecting a regulatory shift in the chronic disease state.

This biphasic cytokine expression pattern—Th2 dominance in early acute lesions transitioning to Th1 predominance in chronic lesions—defines the dynamic immune response in CAD.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs associated with CAD can demonstrate a seasonal or non-seasonal pattern depending on allergen exposure. Pruritus is the hallmark clinical sign.9 In the acute phase, erythema is commonly observed. With chronicity, the skin often develops lichenification and hyperpigmentation secondary to persistent inflammation and mechanical trauma from the scratching, licking, and/or chewing. Recurrent secondary bacterial and yeast infections are common, further intensifying pruritus and cutaneous inflammation.

Focal or patchy alopecia typically results from self-inflicted trauma. Lesions generally follow a characteristic distribution, predominantly affecting the periorbital and perioral facial regions, pinnae, interdigital spaces of the paws, axillae, inguinal region, ventral abdomen, ventral neck, and perianal area.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of canine atopic dermatitis is primarily based on clinical signs and is established through exclusion of other pruritic dermatoses including food allergy dermatitis, environmental/contact dermatitis, flea allergy dermatitis, demodicosis, and sarcoptic mange.

Supportive diagnostic tools include intradermal allergen testing and serum allergen-specific IgE testing, which may aid in identifying relevant environmental allergens.

A presumptive diagnosis of CAD is often reinforced by a positive therapeutic response to interventions such as corticosteroids, hypoallergenic or novel protein diets, and immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive agents (e.g., cyclosporine, oclacitinib, or monoclonal antibodies targeting IL-31).

Histopathological Features

Histological examination of CAD-affected skin reveals focal epidermal hyperplasia and dermal inflammation with marked proliferation of Langerhans cells.12 These antigen-presenting cells are frequently coated with IgE, indicating cutaneous sensitization and supporting the hypothesis of allergen penetration through a defective epidermal barrier.

Mechanism of Action

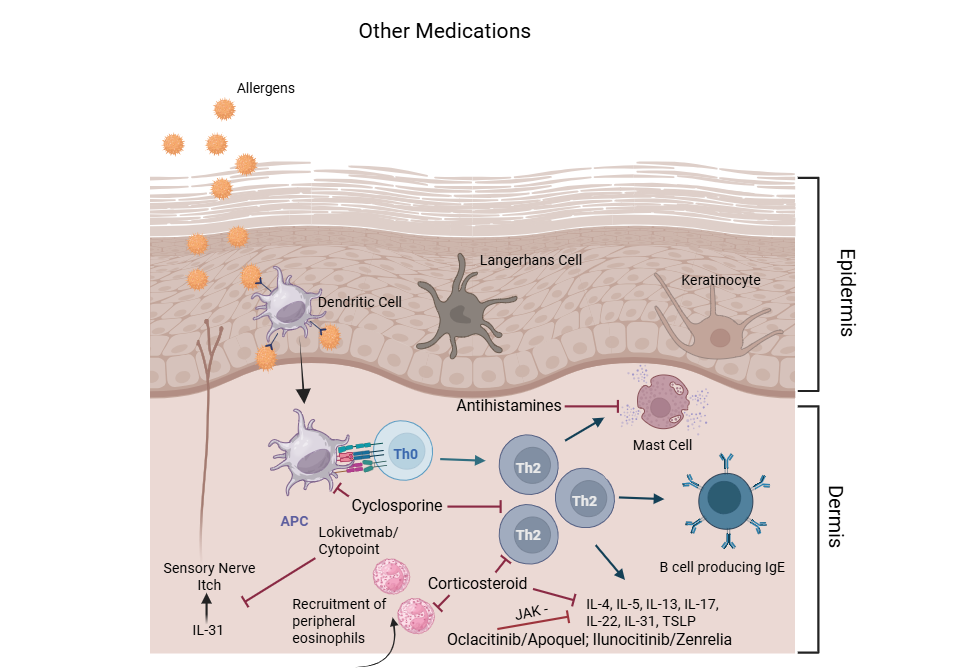

Current Medical Therapies

Standard therapies for CAD include corticosteroids, antihistamines, cyclosporine (Atopica®), JAK inhibitors (oclacitinib/Apoquel®, ilunocitinib/Zenrelia™), monoclonal antibodies against IL-31 (lokivetmab/Cytopoint®) , and patient specific immunotherapy.13,14 Many of these standard therapies target a single pathway and do not resolve the underlying disease pathology, resulting in 20-40% of dogs having incomplete resolution of signs. 13,14

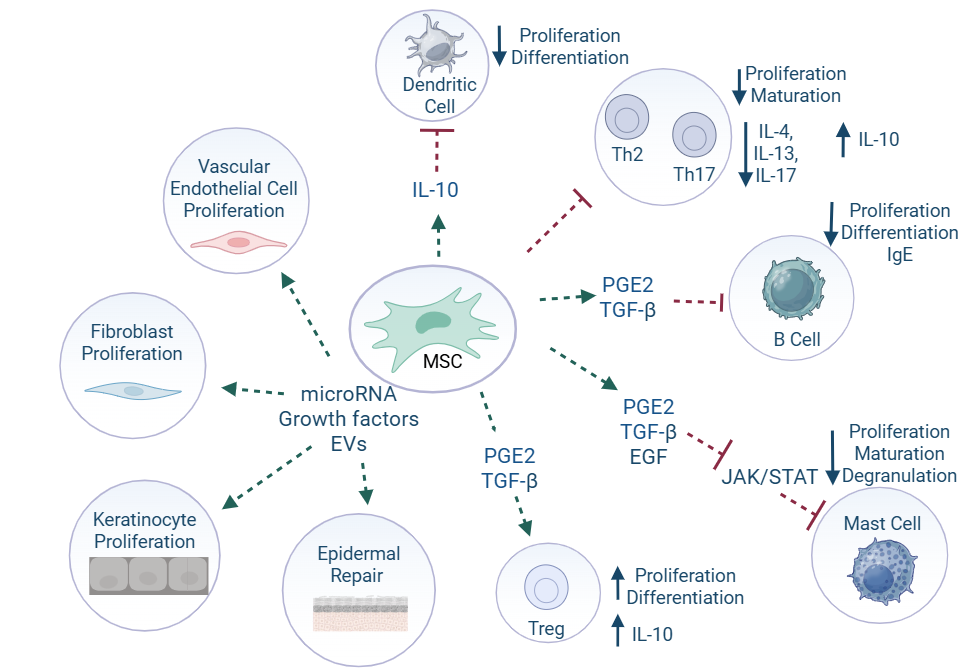

Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal cell (MSC) therapy for CAD

Mesenchymal Stromal (Stem) Cells (MSC) have been investigated as a potential treatment for dogs with AD given their widespread immunomodulatory and reparative properties. Studies have shown a reduction in eosinophils, increase in regulatory T cells (Tregs), reduced IgE and prostaglandin E2 levels, and reduction in epidermal thickness following administration of MSCs. In a Gallant pilot study evaluating uterine-derived MSCs (UMSCs), 71% of dogs achieved treatment success by day 60, indicating IV-administered allogeneic UMSCs reduce and control clinical signs of CAD with a durable benefit lasting 3–6 months.15

Dog with atopic dermatitis enrolled in pilot study evaluating allogeneic uterine-derived MSCs administered intravenously on days 0 and 14.15 Images demonstrate change in lesion appearance from Day 0 (before MSCs) to day 30 and day 60 after MSCs. MSC doses given at Days 0 and 14 (Gallant data on file).

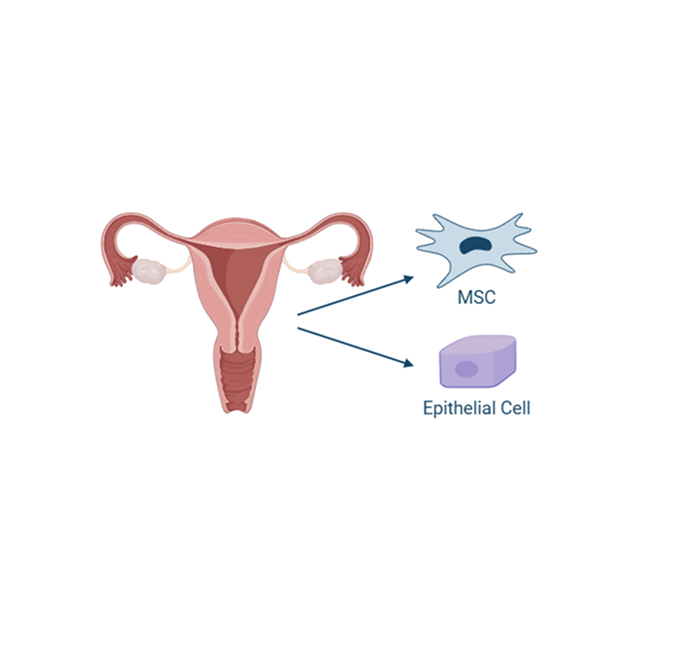

Uterine derived MSCs

The endometrium is the lining of the uterus, and it undergoes cyclic regeneration during each estrous cycle. As a result, it is a readily accessible and renewable source of stem cells. Obtaining allogeneic uterine-derived MSCs is less invasive and less complicated than other sources, making this cell source more feasible for therapeutic applications. Uterine-derived MSCs have also been found to possess potent immunomodulatory properties including regulation of the immune response and reduction in inflammation, crucial for treating inflammatory diseases.

Additionally, MSCs derived from the uterus tend to have low expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens, which makes them less likely to be recognized and attacked by the recipient’s immune system.

Available data to date indicates that UMSCs could provide a novel treatment option for dogs with AD, going beyond treatment of individual clinical signs to provide treatment of the disease at its source.

A deeper look into the life organ

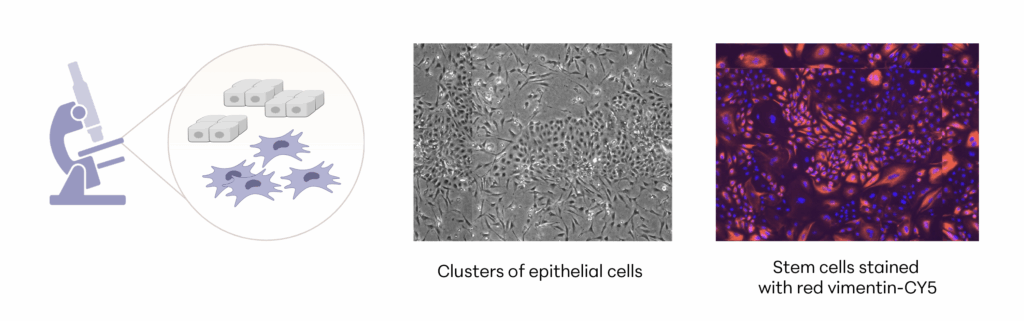

Manufacturing and Potency

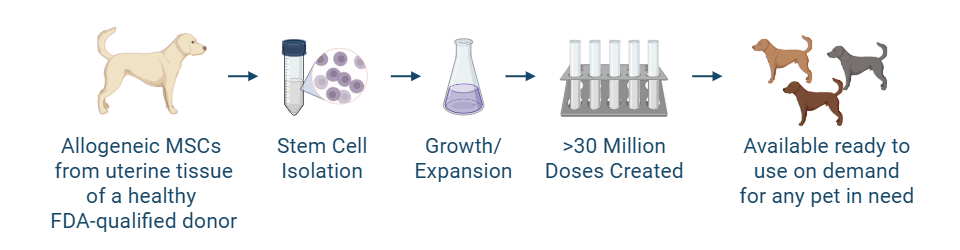

The investigational stem cells to be used in pivotal studies are collected from an FDA-qualified canine donor during a routine spay procedure. The cells are intended to be used in any canine patient as an allogeneic ready to use product. The uterine-derived MSCs have been demonstrated in a matrix of assays to be potent (functional) and directed at the relevant clinical factors in canine AD. Each batch of stem cells is manufactured according to Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) and released with established specifications demonstrating key quality attributes for identity, purity, safety and potency of the drug product.

Allogeneic cells from a FDA qualified donor

References

- Hillier TN, Watt MM, Grimes JA, Berg AN, Heinz JA, Dickerson VM. Dogs receiving cyclooxygenase-2–sparing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or nonphysiologic steroids are at risk of severe gastrointestinal ulceration. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2025;263(3):1-8. doi:10.2460/javma.24.06.0430

- Santoro D. Therapies in Canine Atopic Dermatitis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2019;49(1):9-26. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2018.08.002

- Hillier A, Griffin CE. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (I): incidence and prevalence. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;81(3-4):147-151. doi:10.1016/S0165-2427(01)00296-3

- Cho BS, Kim SB, Kim S, Rhee B, Yoon J, Lee JW. Canine Mesenchymal-Stem-Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Attenuate Atopic Dermatitis. Anim Open Access J MDPI. 2023;13(13):2215. doi:10.3390/ani13132215

- Najera J, Hao J. Recent advance in mesenchymal stem cells therapy for atopic dermatitis. J Cell Biochem. 2023;124(2):181-187. doi:10.1002/jcb.30365

- Kang SJ, Gu NY, Byeon JS, Hyun BH, Lee J, Yang DK. Immunomodulatory effects of canine mesenchymal stem cells in an experimental atopic dermatitis model. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10:1201382. doi:10.3389/fvets.2023.1201382

- Hensel P, Saridomichelakis M, Eisenschenk M, et al. Update on the role of genetic factors, environmental factors and allergens in canine atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2024;35(1):15-24. doi:10.1111/vde.13210

- Yang J, Xiao M, Ma K, et al. Therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells and their derivatives in common skin inflammatory diseases: Atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1092668. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1092668

- Nuttall TJ, Marsella R, Rosenbaum MR, Gonzales AJ, Fadok VA. Update on pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of atopic dermatitis in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2019;254(11):1291-1300. doi:10.2460/javma.254.11.1291

- Labib A, Yosipovitch G, Olivry T. What can we learn from treating atopic itch in dogs? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(2):284-286. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.05.007

- Gober M, Hillier A, Vasquez-Hidalgo MA, Amodie D, Mellencamp MA. Use of Cytopoint in the Allergic Dog. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:909776. doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.909776

- Olivry T, Hill PB. The ACVD task force on canine atopic dermatitis (XVIII): histopathology of skin lesions. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;81(3-4):305-309. doi:10.1016/S0165-2427(01)00305-1

- Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24(5):479. doi:10.1111/vde.12047

- Moyaert H, Van Brussel L, Borowski S, et al. A blinded, randomized clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of lokivetmab compared to ciclosporin in client‐owned dogs with atopic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2017;28(6):593. doi:10.1111/vde.12478

- Black L, Zacharias S, Hughes M, Bautista R, Taechangam N, Sand T. The effect of uterine-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of canine atopic dermatitis: A pilot study. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1011174. doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.1011174