Disease State

Prevalence, Risk Factors & Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disease in dogs, affecting greater than 20% of dogs greater than 1 year of age and up to 80% of dogs greater than 8 years of age in the US.1,2 OA can occur throughout life, and greater than 50% of arthritis cases are observed in dogs aged between 8-13 years of age.3 Some risk factors for OA include breed (Labrador, Golden Retriever, Rottweiler, GSD, Old English Sheepdog), sex (males predominate), being spayed/neutered, and high body weight/obesity.3–5

Factors such as diet may play a role in development as studies have shown that food restricted dogs had lower prevalence and later onset of hip joint osteoarthritis.5 Other risk factors for OA development include humerus-radio-ulnar and hip dysplasia, previous orthopedic surgery, rupture of the cranial cruciate ligament, joint fractures, and incongruencies resulting from trauma or angular deformities of the limbs.6

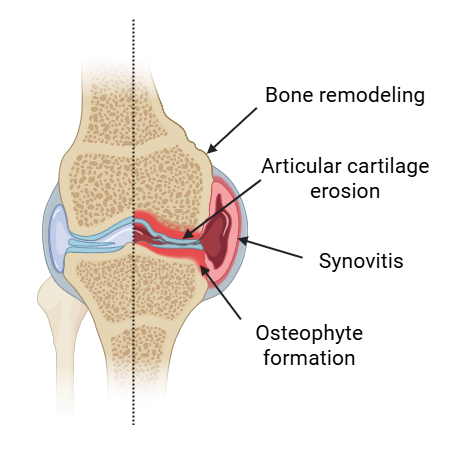

OA does not have to be a normal part of aging. Contrary to the outdated view of OA as merely a “wear and tear” condition, it is now understood to be driven by complex inflammatory processes. OA is a multifactorial joint disorder characterized by cartilage degradation, osteophyte formation, subchondral bone remodeling, synovitis, and alterations in periarticular tissues. Disruption of cartilage homeostasis activates chondrocytes, leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators that contribute to disease initiation and progression. In overweight dogs, leptin and other adipokines have been shown to further amplify joint inflammation, highlighting the metabolic component of OA.7,8 Due to the avascular nature of cartilage and its limited capacity for intrinsic repair, injuries typically heal through fibrocartilage formation, which lacks the biomechanical properties of native hyaline cartilage and accelerates joint degeneration.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs associated with OA in dogs include lameness, difficulty rising, muscle loss, reduced activity, and chronic pain. These symptoms compromise quality of life and the effects of chronic pain can cause behavior changes that may affect the pet and caregiver bond.

Diagnosis

Diagnostics

Osteoarthritis most commonly affects the stifles, hips, and elbows in dogs. Diagnosis is typically made via a combination of physical exam findings, radiographic or CT changes consistent with OA, and in some cases synovial fluid analysis. Radiographs typically demonstrate osteophytes and enthesophytes (new bone formation at the insertion site of musculoskeletal soft tissues. Synovial fluid analysis can be useful in some cases, particularly in stifle OA where there is good diagnostic agreement between synovial fluid effusion and osteophytosis.9

Mechanism of Action

Current Medical Therapies

Management of OA typically requires a multimodal approach. Therapeutic strategies often combine various non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; e.g., carprofen, grapiprant), monoclonal antibodies (e.g., bedinvetmab/Librela), and analgesics (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin, amantadine, memantine, tramadol). Polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (PSGAGs) such as Adequan and nutraceuticals including omega-3 fatty acids, type II collagen, chondroitin sulfate, and fish oil-based supplements are frequently incorporated. Weight loss is encouraged in overweight dogs. Adjunctive therapies, including acupuncture, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, laser therapy, and structured physical rehabilitation may be beneficial. Injectable biologics including platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and hyaluronic acid (HA) are employed in selected cases. While these interventions can modulate pain and inflammation to improve clinical signs, they do not reverse cartilage degeneration. Consequently, disease progression continues and therapeutic efficacy may diminish in advanced stages of OA.

Stem cell therapy of OA

Historically, stem cell therapy with autologous (donor is recipient) adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has shown a potential role in the management of OA in dogs. However, factors including patient age, obesity, and systemic disease may affect stem cell quantity and quality for some dogs. Allogeneic (donor is the same species as the recipient) MSCs sourced from young, healthy donors help ensure greater consistency and potency. Advancements in allogeneic MSC therapy development will potentially bring a ready-to-use on-demand or “off-the-shelf” MSC product for canine OA.

MSCs can be administered to treat OA via intra-articular (IA) or intravenous (IV) routes, IV administration is less invasive, does not require sedation or anesthesia, and enables a systemic delivery of cells to potentially treat multiple joints through a single injection. IA delivery offers direct access to affected joints, with more localized action. Importantly however, MSCs have demonstrated the capacity to home to inflamed joints following IV administration in the dog.10

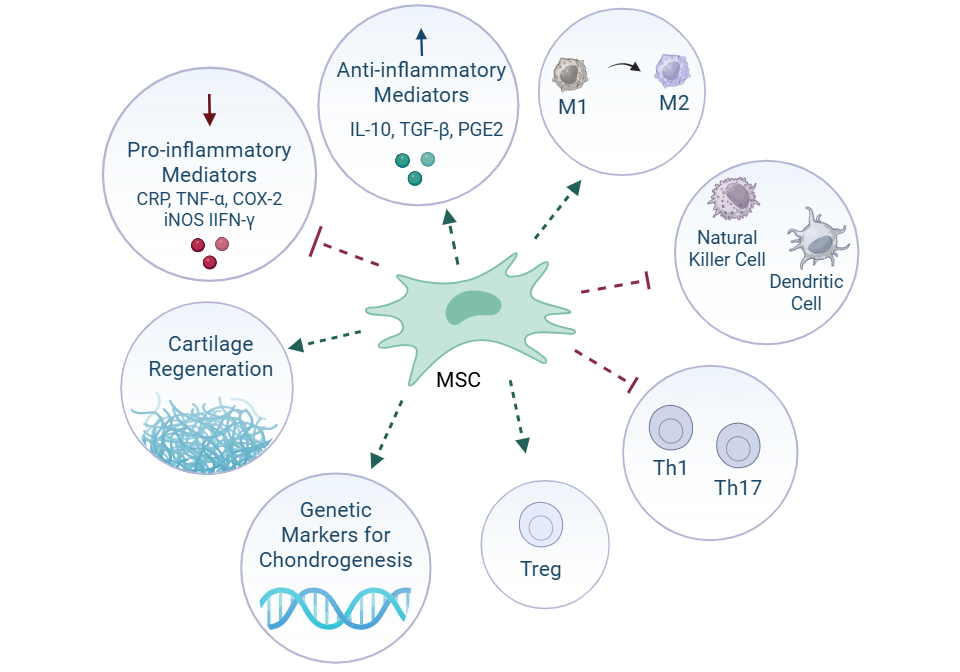

Mechanistically, MSCs exert immunomodulatory and regenerative effects primarily through paracrine signaling. They downregulate key inflammatory mediators such as C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). In addition to modulating inflammation, MSCs promote tissue repair and chondrogenesis, with upregulation of cartilage-specific genetic markers observed post-treatment. These regenerative properties position stem cells as a potential disease-modifying treatment option, which would distinguish them from conventional OA therapies that primarily target symptom control.

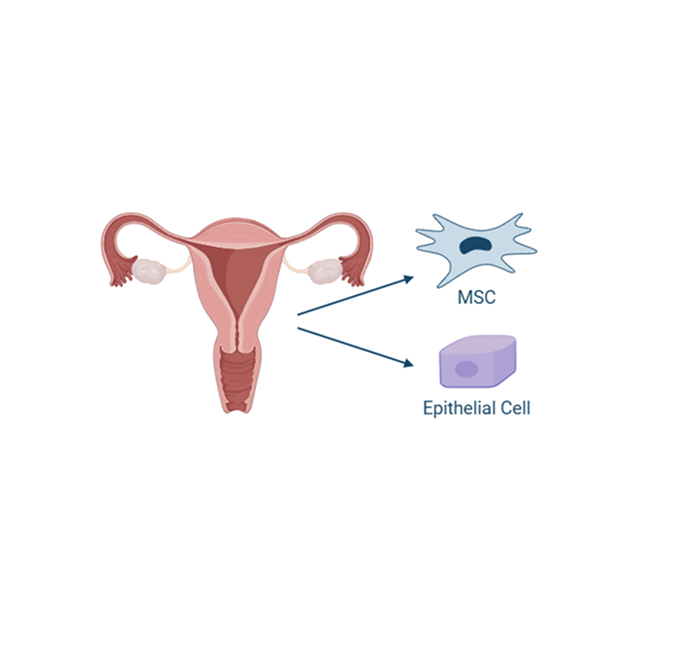

Uterine derived MSCs

The endometrium is the lining of the uterus, and it undergoes cyclic regeneration during each estrous cycle. As a result, it is a readily accessible and renewable source of stem cells. Obtaining allogeneic uterine-derived MSCs is less invasive and less complicated than other sources, making this cell source more feasible for therapeutic applications. Uterine-derived MSCs have also been found to possess potent immunomodulatory properties, including regulation of the immune response and reduction in inflammation, crucial for treating inflammatory diseases.

Additionally, MSCs derived from the uterus tend to have low expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens, which makes them less likely to be recognized and attacked by the recipient’s immune system.

Available data to date suggests that use of UMSCs could provide a novel treatment option for dogs with OA, going beyond treatment of individual clinical signs to provide treatment of the disease at its source, potentially enhancing the patient’s quality of life.

A deeper look into the life organ

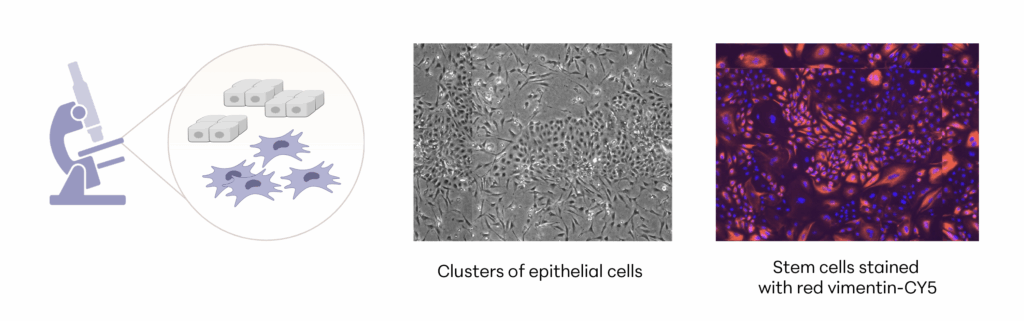

Manufacturing and Potency

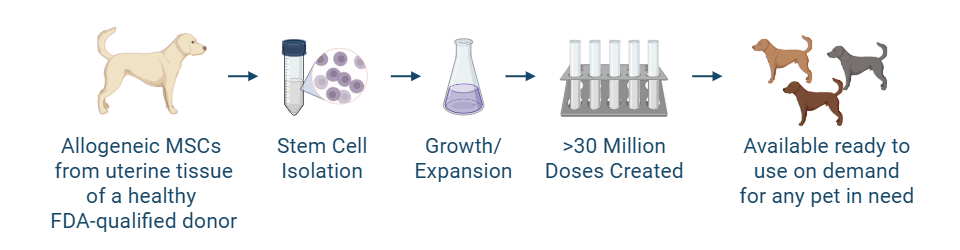

The investigational stem cells to be used in pivotal studies are collected from an FDA-qualified canine donor during a routine spay procedure. The cells are intended to be used in other canine patients as an allogeneic ready to use product. The uterine-derived MSCs have been demonstrated in a matrix of assays to be potent (functional) and directed at the relevant clinical factors in canine OA. Each batch of stem cells is manufactured according to Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMP) and is released with established specifications demonstrating key quality attributes for identity, purity, safety and potency of the drug product.

Allogeneic cells from a FDA qualified donor

References

- Wright A, Snyder L, Knights K, et al. A Protocol for the Isolation, Culture, and Cryopreservation of Umbilical Cord-Derived Canine Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: Role of Cell Attachment in Long-Term Maintenance. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29(11):695-713. doi:10.1089/scd.2019.0145

- Johnston SA. Osteoarthritis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1997;27(4):699-723. doi:10.1016/S0195-5616(97)50076-3

- Mele E. Epidemiologie der Osteoarthritis/Osteoarthrose. Vet Focus. 2007;17(3):4-10.

- Anderson KL, O’Neill DG, Brodbelt DC, et al. Prevalence, duration and risk factors for appendicular osteoarthritis in a UK dog population under primary veterinary care. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5641. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-23940-z

- Smith GK, Paster ER, Powers MY, et al. Lifelong diet restriction and radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis of the hip joint in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2006;229(5):690-693. doi:10.2460/javma.229.5.690

- Amaral AR, Risolia LW, Rentas MF, et al. Translating Human and Animal Model Studies to Dogs’ and Cats’ Veterinary Care: Beta-Glucans Application for Skin Disease, Osteoarthritis, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Management. Microorganisms. 2024;12(6):1071. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12061071

- Dumond H, Presle N, Terlain B, et al. Evidence for a key role of leptin in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3118-3129. doi:10.1002/art.11303

- Theyse LFH, Mazur EM. Osteoarthritis, adipokines and the translational research potential in small animal patients. Front Vet Sci. 2024;11:1193702. doi:10.3389/fvets.2024.1193702

- Ramírez-Flores GI, Del Angel-Caraza J, Quijano-Hernández IA, Hulse DA, Beale BS, Victoria-Mora JM. Correlation between osteoarthritic changes in the stifle joint in dogs and the results of orthopedic, radiographic, ultrasonographic and arthroscopic examinations. Vet Res Commun. 2017;41(2):129-137. doi:10.1007/s11259-017-9680-2

- Beerts C, Pauwelyn G, Depuydt E, et al. Homing of radiolabelled xenogeneic equine peripheral blood-derived MSCs towards a joint lesion in a dog. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1035175. doi:10.3389/fvets.2022.1035175